The rib cage is the central "core" between the neck above, the low back below, and the shoulders on each side. Any problems with the rib cage, any tightness, lack of full motion, or weakness, will force the neck, low back, and shoulders to work too hard. Much neck pain, shoulder pain, and low back pain has its root in the rib cage. It really is the forgotten center of the body.

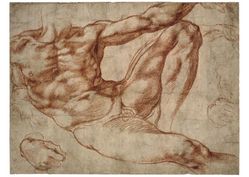

Michelangelo started his drawings of the human body with the torso, the ribs and upper region of the abdomen, because in his mind it was the torso that dictated the rest of the display of the body. He would often just barely sketch the face and limbs, even leaving them blank many times, in order to ensure his portrayal of the torso was accurate.

In mythology and ancient physiology around the world, the trunk and rib cage carries very significant meaning. The ancient understanding was that the trunk housed our consciousness. Who we think we are, what we might nowadays call "the ego," resides not in our heads, as we imagine it today, but in the rib cage. Ancient Greeks imagined the soul to be in the head (as discussed in an earlier post Your Head Has a Mind of Its Own), but a person's conscious actions and thoughts came out of the rib cage. The ancient Greeks called this region the phrenes, which means lungs. (We get the word schizophrenic from these old ideas. Schizophrenic means split lungs: the consciousness is split.)

In the Old Testament of the Bible, the ruah was the vital breath that makes humans living creatures. It lives in the rib cage. For ancient people around the world, it was the rib cage and the breath inside it that in many ways is the human. It is the breath that made this concept obvious to ancient people. Breathing changes with our emotional state, and it is the breath that comes out through the throat to generate our voice. What a person says is generated from within the rib cage both literally as a mechanical reality, and figuratively in these ancient ways of imagining how the body works.

In the modern world, "knowing" what we know about the anatomy of the body, stuffing our entire existence into the brain, forsaking the rest of the body as dead matter, it isn't surprising that unless one has suffered with rib pain, one is unlikely to have done anything but completely ignore this region of the body. We might even imagine that rib pain is a scream from the ruah, the phrenes, the ribs, or one's own heart, for attention. It wants to be imagined as an important part of your body. It wants you to know that everything you do, say, and even think, comes from deep within its breath. It wants you to know that without its breathing, you'd be gone very quickly from this world.

Breathing is the obvious way to tend to the rib cage. There are various schools of thought on how we should breathe. A singing instructor might tell us to breathe from the diaphragm. A Pilates instructor would tell us use "Pilates' breathing." A yoga instructor may tell us to breathe from the belly. But I think it's extremely foolish to think that we have any real understanding of how breathing affects the body and how to "breathe properly," as if we could consciously breathe in different ways without severely interfering with how the body functions. I spent three years "breathing properly" according to one school of thought and the result was a number of stiff ribs and a habitually poor breathing pattern that took me years to unravel.

A much better option is to spend a few minutes each day breathing in a number of different ways, opening and closing each part of the rib cage. This gives the rib cage some attention and simultaneously doesn't attempt to "fix" the way we breathe. Instead, it gives the rib cage options for breathing, and then trusts the rib cage to breathe how it needs to breathe at any given moment. Let's keep the conscious mind where it belongs: in the rib cage, not thinking about the rib cage.

The following simple breathing exercises can help to get the entire rib cage opened, giving it its full options. Spend 30 seconds (or more) in each of five positions while alternatively breathing deeply into your chest and then deeply into your abdomen. Focus on expanding the chest in three dimensions: forward and backward, upward and downward, and to the right and left. Do the same for the belly when breathing into the belly. The five positions to use are: 1) lying face-up with your knees bent (not shown), 2) in the Cobra pose (left), 3) in the Child's pose (upper right), and 4 and 5) lying twisted on one side and then on the other (lower right).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed